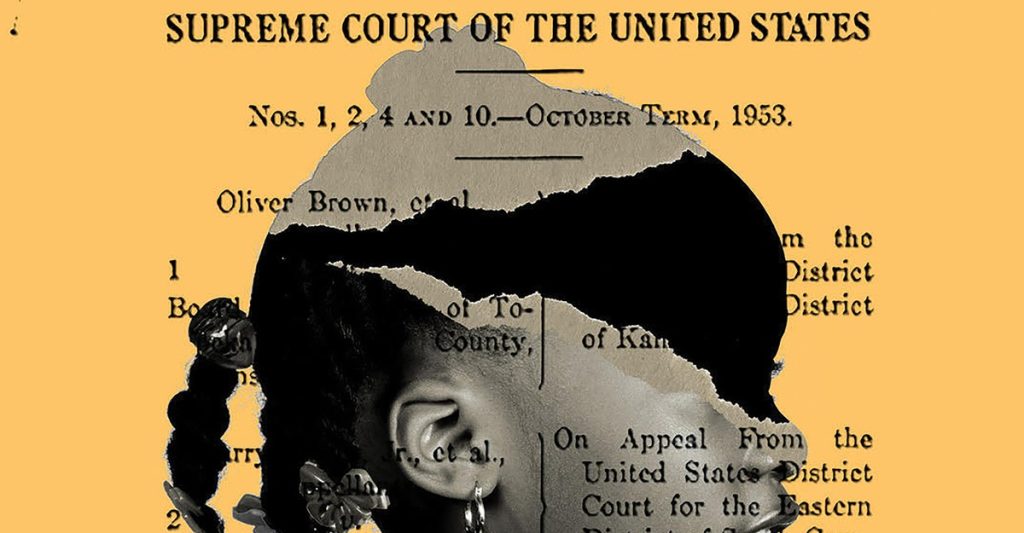

On Might 17, 1954, a nervous 45-year-old lawyer named Thurgood Marshall took a seat within the Supreme Courtroom’s gallery. The founder and director of the NAACP Authorized Protection and Instructional Fund hoped to study that he had prevailed in his pivotal case. When Chief Justice Earl Warren introduced the Courtroom’s opinion in Brown v. Board of Training, Marshall couldn’t have identified that he had additionally received what continues to be broadly thought of probably the most vital authorized resolution in American historical past. Listening to Warren declare “that within the area of public training the doctrine of ‘separate however equal’ has no place” delivered Marshall right into a state of euphoria. “I used to be so comfortable, I used to be numb,” he stated. After exiting the courtroom, he joyously swung a small boy atop his shoulders and galloped across the austere marble corridor. Later, he informed reporters, “It’s the best victory we ever had.”

For Marshall, the “we” who triumphed in Brown certainly referred not solely, and even primarily, to himself and his Authorized Protection Fund colleagues, however to all the Black race, on whose behalf they’d toiled. And Black People did certainly discover Brown exhilarating. Harlem’s Amsterdam Information, echoing Marshall, referred to as Brown “the best victory for the Negro folks because the Emancipation Proclamation.” W. E. B. Du Bois acknowledged, “I’ve seen the unattainable occur. It did occur on Might 17, 1954.” When Oliver Brown discovered of the result within the lawsuit bearing his surname, he gathered his household close to, and credited divine windfall: “Thanks be to God for this.” Martin Luther King Jr. inspired Montgomery’s activists in 1955 by invoking Brown: “If we’re incorrect, then the Supreme Courtroom of this nation is incorrect. If we’re incorrect, the Structure of america is incorrect. If we’re incorrect, God Almighty is incorrect.” Many Black folks seen the opinion with such awe and reverence that for years afterward, they threw events on Might 17 to have fun Brown’s anniversary.

Over time, nevertheless, some started questioning what precisely made Brown worthy of celebration. In 1965, Malcolm X in his autobiography voiced an early criticism of Brown: It had yielded valuable little college desegregation over the earlier decade. Calling the choice “one of many best magical feats ever carried out in America,” he contended that the Courtroom’s “masters of authorized phrasing” had used “trickery and magic that informed Negroes they had been desegregated—Hooray! Hooray!—and on the identical time … informed whites ‘Listed below are your loopholes.’ ”

However that criticism paled as compared with the anti-Brown denunciation in Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton’s Black Energy: The Politics of Liberation two years later. They condemned not Brown’s implementation, however its orientation. The basic goal of integration should be deserted as a result of it was pushed by the “assumption that there’s nothing of worth within the black neighborhood,” they maintained.

To sprinkle black kids amongst white pupils in outlying colleges is at finest a stop-gap measure. The aim is to not take black kids out of the black neighborhood and expose them to white middle-class values; the aim is to construct and strengthen the black neighborhood.

Though Black skeptics of the mixing superb originated on the far left, Black conservatives—together with the economist Thomas Sowell—have extra lately ventured associated critiques. Probably the most outstanding instance is Marshall’s successor on the Supreme Courtroom, Justice Clarence Thomas. In 1995, 4 years after becoming a member of the Courtroom, Thomas issued a blistering opinion that opened, “It by no means ceases to amaze me that the courts are so keen to imagine that something that’s predominantly black should be inferior.”

Determined efforts to advertise college integration, Thomas argued, stemmed from the misperception that identifiably Black colleges had been one way or the other doomed to fail due to their racial composition. “There isn’t a cause to suppose that black college students can’t study as effectively when surrounded by members of their very own race as when they’re in an built-in atmosphere,” he wrote. Taking a web page from Black Energy’s communal emphasis, Thomas argued that “black colleges can operate as the middle and image of black communities, and supply examples of impartial black management, success, and achievement.” In a 2007 opinion, he extolled Washington, D.C.’s all-Black Dunbar Excessive College—which despatched dozens of graduates to the Ivy League and its ilk throughout the early twentieth century—as a paragon of Black excellence.

Within the 2000s, as Brown crept towards its fiftieth anniversary, Derrick Bell of the NYU College of Regulation went as far as to allege that the opinion had been wrongly determined. For Bell, who had sharpened his abilities as an LDF lawyer, Brown’s “integration ethic centralizes whiteness. White our bodies are represented as one way or the other exuding an intrinsic worth that percolates into the ‘hearts and minds’ of black kids.” Warren’s opinion within the case ought to have affirmed Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate however equal” regime, Bell wrote, but it surely ought to have insisted on real equality of expenditures, reasonably than allowing the sham equality of yore that consigned Black college students to shoddy lecture rooms in dilapidated buildings. He acknowledged, although, that his jaundiced account put him at odds with dominant American authorized and cultural attitudes: “The Brown resolution,” he famous, “has turn out to be so sacrosanct in legislation and within the beliefs of most People that any critic is deemed wrongheaded, even a traitor to the trigger.”

In her New E book, Built-in: How American Faculties Failed Black Youngsters, Noliwe Rooks provides to a rising literature that challenges the portrayal of the choice as “a major civil rights–period win.” Rooks, the chair of the Africana-research division at Brown College, provides an uncommon mix of historic examination and household memoir that usually amplifies the issues articulated by prior desegregation discontents. The consequence deserves cautious consideration not for its progressive arguments, however as an impassioned, arresting instance of how Brown skepticism, which initially gained traction on the fringes of Black life, has come to carry appreciable attraction inside the Black mental mainstream.

As lately as halfway by way of the primary Trump administration, Rooks would have positioned herself firmly within the conventional pro-Brown camp, satisfied that addressing racial inequality in training might finest be pursued by way of integration. However touring a number of years in the past to advertise a ebook that criticized how personal colleges usually thwart significant racial integration, she repeatedly encountered viewers members who disparaged her core embrace of integration. Many times, she heard from Black dad and mom that “the trauma their kids skilled in predominantly white colleges and from white academics was generally extra dangerous than the undereducation occurring in segregated colleges.”

The onslaught dislodged Rooks’s religion within the worth of latest integration, and even of Brown itself. She now reveals the convert’s zeal. Brown, she writes, needs to be seen as “an assault on Black colleges, politics, and communities, which meant it was an assault on the pillars of Black life.” For some Black residents, the choice acted as “a wrecking ball that crashed by way of their communities and, like a pendulum, continues to swing.”

Rooks emphasizes the plight of Black educators, who disproportionately misplaced their positions in Brown’s aftermath due to college consolidations. Earlier than Brown, she argues, “Black academics didn’t see themselves as simply educating music, studying, or science, but additionally as activists, organizers, and freedom fighters who dreamed of and fought for an equitable world for future generations”; they served as fashions who confirmed “Black kids find out how to battle for respect and societal change.”

Endorsing considered one of Black Energy’s analogies, she maintains that college integration meant that “as small a quantity as potential of Black kids had been, like pepper on popcorn, frivolously sprinkled atop rich, white college environments, whereas most others had been left behind.” Even for these ostensibly lucky few flecks of pepper, Rooks insists, offering the white world’s seasoning turned out to be a extremely unsure, harmful endeavor. She makes use of her father’s disastrous experiences with integration to look at what she regards because the perils of all the enterprise. After excelling in all-Black academic environments, together with as an undergraduate at Howard College, Milton Rooks grew to become considered one of a really small variety of Black college students to enroll on the Golden Gate College College of Regulation within the early Nineteen Sixties.

Despatched by his hopeful dad and mom “over that racial wall,” Milton encountered hostility from white professors, who doubted his mental capability, Rooks recounts, and “spit him again up like a chunk of meat poorly digested.” She asserts that the ordeal not solely prompted him to drop out of legislation college but additionally spurred his descent into alcoholism. Rooks extrapolates additional, writing:

Milton’s expertise mirrored the trauma Black college students suffered as they desegregated public colleges in states above the Mason-Dixon Line, the place shows of racism had been usually mocking, disdainful, pitying, and sword sharp of their skill to chop the unsuspecting into tiny bits. It destroyed confidence, shook will, sowed doubt, murdered souls—quietly, positive, however nonetheless as fully as might a mob of white racists setting their cowardice, rage, and anger unfastened upon the defenseless.

The harms that modern built-in academic environments inflict upon Black college students may be tantamount, in her view, to the harms imposed upon the numerous Black college students who’re compelled to attend monoracial, woeful city excessive colleges. To make this level, Rooks recounts her personal wrestle to appropriate the misplacement of her son, Jelani, in a low-level math class in Princeton, New Jersey’s public-school system throughout the aughts (when she taught at Princeton College). She witnessed different Black dad and mom meet with an identical lack of help in guiding their kids to the academically demanding programs that would propel them to elite schools. In Jelani’s case, she had proof that academics’ “emotions had been hardening towards him.” He led a lifetime of relative security and financial privilege, and felt comfy amongst his white classmates and associates, she permits, at the same time as she additionally stresses that what he “skilled wasn’t the violence of poverty; it was one thing else equally devastating”:

We knew that poor, working-class, or city communities weren’t the one locations the place Black boys are terrorized and traumatized. We knew that the unfamiliarity of his white associates with some other Black folks would at some point turn out to be a problem in our house. We knew that weapons weren’t the one solution to homicide a soul.

Annoyed with Princeton’s public colleges, Rooks ultimately enrolled Jelani in an elite personal highschool the place, she notes, he additionally endured racial harassment—and from which he graduated earlier than making his solution to Amherst Faculty.

seven many years have now elapsed because the Supreme Courtroom’s resolution in Brown. Given the stubbornly persistent phenomenon of underperforming predominantly Black colleges all through the nation, arguing that Brown’s potential has been absolutely realized could be absurd. Regrettably, the Warren Courtroom declined to advance probably the most highly effective conception of Brown when it had the chance to take action: Its infamously obscure “all deliberate velocity” method allowed state and native implementation to be delayed and opposed for a lot too lengthy. In its flip, the Burger Courtroom supplied an emaciated conception of Brown’s that means, one which permitted many non-southern jurisdictions to keep away from pursuing desegregation applications. Rooks deftly sketches this lamentable, sobering historical past.

Disenchantment with Brown’s academic efficacy is thus solely comprehensible. But to counsel that the Supreme Courtroom didn’t go far sufficient, quick sufficient in galvanizing racially constructive change in American colleges after Brown is one factor. To counsel that Brown one way or the other took a incorrect flip is sort of one other.

Rooks doesn’t deny that integration succeeded in narrowing the racial achievement hole. However like different Brown critics, she however idealizes the period of racial segregation. Close to Built-in ’s conclusion, Rooks contends that “too few of us have a reminiscence of segregated Black colleges because the beating coronary heart of vibrant Black communities, enabling college students to compose lives of concord, melody, and rhythm and sustained Black life and dignity.” However this declare will get issues precisely backwards. The courageous individuals who bore segregation’s brunt believed that Jim Crow represented an assault on Black life and dignity, and that Brown marked a sea change in Black self-conceptions.

Desegregation’s detractors routinely elevate the glory days of D.C.’s Dunbar Excessive College, however they refuse to heed the teachings of its most distinguished graduates. Charles Hamilton Houston—Dunbar class of 1911, who went on to turn out to be valedictorian at Amherst and the Harvard Regulation Evaluate’s first Black editor—however devoted his life to eradicating Jim Crow as an NAACP litigator and Thurgood Marshall’s mentor in his work contesting academic segregation. Sterling A. Brown—Dunbar class of 1918, who graduated from Williams Faculty earlier than turning into a distinguished poet and professor—however wrote the next in 1944, one decade earlier than Brown:

Negroes acknowledge that the phrase “equal however separate lodging” is a fantasy. They’ve identified Jim Crow a very long time, and so they know Jim Crow means scorn and never belonging.

A lot as they valued having proficient, caring academics, these males understood racial segregation intimately, and so they detested it.

Within the Nineteen Nineties, Nelson B. Rivers III, an unheralded NAACP official from South Carolina, memorably heaved buckets of chilly water on those that had been starting to surprise, “ Was integration the best factor to do? Was it price it? Was Brown resolution?” Rivers dismissed such questions as “asinine,” and continued:

To this present day, I can keep in mind bus drivers pulling off and blowing smoke in my mom’s face. I can keep in mind the again of the bus, coloured water fountains … I can hear a cop telling me, “Take your black butt again to nigger city.” What I inform folks … is that there are a variety of romanticists now who need to take this journey down Reminiscence Lane, and so they need to return, and I inform the younger those who anyone who needs to take you again to segregation, ensure you get a round-trip ticket since you received’t keep.

Nostalgia for the pre-Brown period wouldn’t train practically so highly effective a grip on Black America right this moment if its adherents targeted on its detailed, pervasive inhumanities reasonably than counting on gauzy glimpses.

Nobody has pressed this level extra vividly than Robert L. Carter, who labored alongside Marshall on the LDF earlier than ultimately turning into a distinguished federal decide. He understood that to seek for Brown’s influence completely within the academic area is mistaken. As a substitute, he emphasised that Brown fomented a broad-gauge racial revolution all through American public life. Regardless of Chief Justice Warren formally writing the opinion to use completely to training, its assault on segregation has—paradoxically—been most efficacious past that unique context.

“The psychological dimensions of America’s race relations downside had been fully recast” by Brown, Carter wrote. “Blacks had been not supplicants looking for, pleading, begging to be handled as full-fledged members of the human race; not had been they interesting to morality, to conscience, to white America’s higher instincts,” he famous. “They had been entitled to equal therapy without any consideration below the legislation; when such therapy was denied, they had been being disadvantaged—in actual fact robbed—of what was legally theirs. Because of this, the Negro was propelled right into a stance of insistent militancy.”

Even inside the academic sphere, although, it’s profoundly misguided to say that Black college students who attend stable, meaningfully built-in colleges encounter environments as corrosive as, or worse than, these dealing with college students trapped in ghetto colleges. This damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t evaluation suggests a whole cohort caught in the identical boat, when its many members aren’t even in the identical ocean. The Black scholar marooned in a poor and violent neighborhood, with cause to worry precise homicide, envies the Black scholar attending a rigorous, built-in college who worries about metaphorical “soul homicide.” All struggles aren’t created equal.

This text seems within the April 2025 print version with the headline “Was Integration the Unsuitable Aim?”

While you purchase a ebook utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.